Change Management from tutor2u

Saturday, 27 January 2018

Wednesday, 24 January 2018

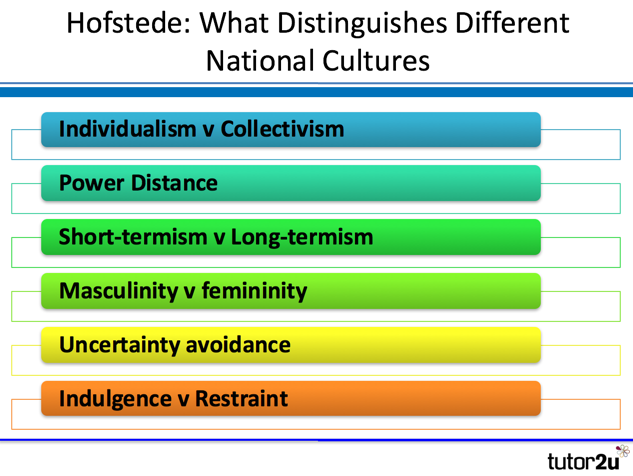

Business Culture - Hofstede Culture

Social psychologist Geert Hofstede has conducted extensive research into the different categories of culture that help distinguish the ways business is conducted between different nations.

Hofstede carried out research amongst over 100,000 employees working around the world for IBM.

He attempted to categorise cultures of different nationalities working at IBM

Hofstede has extended the categories to six based on his latest research

Individualism v Collectivism

Some societies value the performance of individuals

For others, it is more important to value the performance of the team

Has important implications for financial rewards at work (e.g. individual bonuses v profit-sharing for bigger groups)

Power Distance

This considers the extent to which inequality is tolerated and whether there is a strong sense of position and status

A high PD score would indicate a national culture that accepts and encourages bureaucracy and a high respect for authority and rank

A lower PD score would suggest a national culture that encourages flatter organisational structures & a greater emphasis on personal responsibility and autonomy

Long-term orientation

This category is concerned with the different emphases national cultures have on the time horizons for business planning, objectives & performance

Some countries place greater emphasis on short-term performance (so-called short-termism), with financial and other rewards biased towards a period of just a few months or years.

Other countries take a much longer-term perspective, which is likely to encourage more long-term thinking.

The key implication of this category is the impact on investment decisions and risk-taking

Masculinity v Femininity

This somewhat unfortunately-named category considers the differences in decision-making style

Hofstede linked what he called a “masculine” approach to a hard-edged, fact-based and aggressive style decision-making

By contrast, ”feminine” decision-making involved a much greater degree of consultation and intuitive analysis

Uncertainty Avoidance

This category essentially considers the different attitudes to risk-taking between countries

Hofstede looked at the level of anxiety people feel when in uncertain or unknown situations

Low levels of uncertainty avoidance indicate a willingness to accept more risk, work outside the rules and embrace change. This might indicate a more entrepreneurial national culture

Higher levels of uncertainty avoidance would suggest more support for rules, data, clarity of roles and responsibilities etc. These cultures might be less entrepreneurial as a consequence

Indulgence v Restraint

Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun

Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms

Labels:

culture,

Handy's organisational culture,

hofstede

Monday, 22 January 2018

Business Culture

Charles Handy, a leading authority on organisational culture, defined four different kinds of culture:

Power culture

Role culture

Task culture

Person culture

Let's summarise what each of those kinds of organisational culture mean.

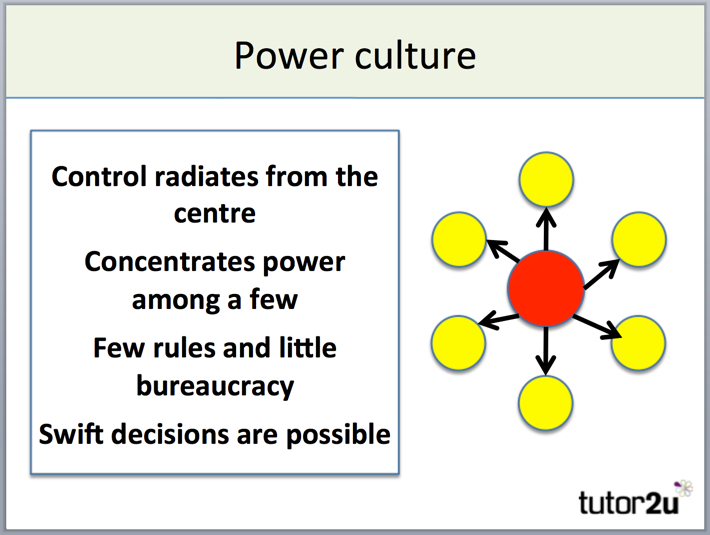

Power Culture

In an organisation with a power culture, power is held by just a few individuals whose influence spreads throughout the organisation.

There are few rules and regulations in a power culture. What those with power decide is what happens. Employees are generally judged by what they achieve rather than how they do things or how they act. A consequence of this can be quick decision-making, even if those decisions aren't in the best long-term interests of the organisation.

A power culture is usually a strong culture, though it can swiftly turn toxic. The collapse of Enron, Lehman Brothers and RBS is often attributed to a strong power culture.

Role Culture

Organisations with a role culture are based on rules. They are highly controlled, with everyone in the organisation knowing what their roles and responsibilities are. Power in a role culture is determined by a person's position (role) in the organisational structure.

Role cultures are built on detailed organisational structures which are typically tall (not flat) with a long chain of command. A consequence is that decision-making in role cultures can often be painfully-slow and the organisation is less likely to take risks. In short, organisations with role cultures tend to be very bureaucratic.

Task Culture

Task culture forms when teams in an organisation are formed to address specific problems or progress projects. The task is the important thing, so power within the team will often shift depending on the mix of the team members and the status of the problem or project.

Whether the task culture proves effective will largely be determined by the team dynamic. With the right mix of skills, personalities and leadership, working in teams can be incredibly productive and creative.

Person Culture

In organisations with person cultures, individuals very much see themselves as unique and superior to the organisation. The organisation simply exists in order for people to work. An organisation with a person culture is really just a collection of individuals who happen to be working for the same organisation.

Sunday, 14 January 2018

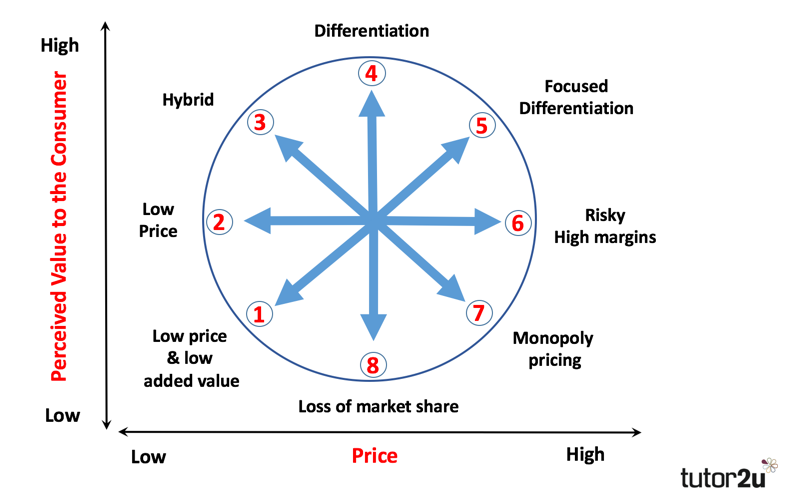

Bowman's Strategic Clock

Bowman’s Strategic Clock is a model that explores the options for strategic positioning – i.e. how a product should be positioned to give it the most competitive position in the market.

The purpose of the clock is to illustrate that a business will have a variety of options of how to position a product based on two dimensions – price and perceived value.

The Strategic Clock looks like this:

Let’s look briefly at each position on the clock

Low Price and Low Value Added (Position 1)

Not a very competitive position for a business. The product is not differentiated and the customer perceives very little value, despite a low price. This is a bargain basement strategy. The only way to remain competitive is to be as “cheap as chips” and hope that no-one else is able to undercut you.

Low Price (Position 2)

Businesses positioning themselves here look to be the low-cost leaders in a market. A strategy of cost minimisation is required for this to be successful, often associated with economies of scale. Profit margins on each product are low, but the high volume of output can still generate high overall profits. Competition amongst businesses with a low price position is usually intense – often involving price wars.

Hybrid (Position 3)

As the name implies, a hybrid position involves some element of low price (relative to the competition), but also some product differentiation. The aim is to persuade consumers that there is good added value through the combination of a reasonable price and acceptable product differentiation. This can be a very effective positioning strategy, particularly if the added value involved is offered consistently.

Differentiation (Position 4)

The aim of a differentiation strategy is to offer customers the highest level of perceived added value. Branding plays a key role in this strategy, as does product quality. A high quality product with strong brand awareness and loyalty is perhaps best-placed to achieve the relatively prices and added-value that a differentiation strategy requires.

Focused Differentiation (Position 5)

This strategy aims to position a product at the highest price levels, where customers buy the product because of the high perceived value. This the positioning strategy adopted by luxury brands, who aim to achieve premium prices by highly targeted segmentation, promotion and distribution. Done successfully, this strategy can lead to very high profit margins, but only the very best products and brands can sustain the strategy in the long-term.

Risky High Margins (Position 6)

This is a high risk positioning strategy that you might argue is doomed to failure – eventually. With this strategy, the business sets high prices without offering anything extra in terms of perceived value. If customers continue to buy at these high prices, the profits can be high. But, eventually customers will find a better-positioned product that offers more perceived value for the same or lower price. Other than in the short-term, this is an uncompetitive strategy. Being able to sell for a price premium without justification is tough in any normal competitive market.

Monopoly Pricing (Position 7)

Where there is a monopoly in a market, there is only one business offering the product. The monopolist doesn’t need to be too concerned about what value the customer perceives in the product – the only choice they have is to buy or not. There are no alternatives. In theory the monopolist can set whatever price they wish. Fortunately, in most countries, monopolies are tightly regulated to prevent them from setting prices as they wish.

Loss of Market Share (Position 8)

This position is a recipe for disaster in any competitive market. Setting a middle-range or standard price for a product with low perceived value is unlikely to win over many consumers who will have much better options (e.g. higher value for the same price from other competitors).

Overview

Looking at the Strategy Clock in overview, you should be able to see that three of the positions (6, 7 and 8) are uncompetitive. These are the ones where price is greater than perceived value. Provided that the market is operating competitively, there will always be competitors that offer a higher perceived value for the same price, or the same perceived value for a lower price.

Monday, 8 January 2018

Boston Matrix & Samsung

A great post on South Korean multinational giant Samsung for Business Students.

Samsung is a highly diversified multinational that is the most significant firm in the South Korean economy. It has achieved a strong record of improved profitability, quarter after quarter, as demand for its product portfolio has grown, particularly mobile devices.

However, in January 2014 it announced that it expected to suffer a fall in profits:

Samsung's pre-earnings guidance showed it expected to make an operating profit of 8.3 trillion won ($7.8bn; £4.8bn) for the last quarter of 2013, down 18% from the previous three months.

What were the implications for Samsung following their announcement?

We can use the Boston Matrix as a model of strategic choice to outline some of the issues and options for Samsung.

For Samsung, mobile devices became the most significant generator of profits, contributing around two-thirds of overall company profits in recent quarters. For some time, Samsung's portfolio of smartphones and tablets had been the rising stars of the Samsung product portfolio as demand soared in both developed and emerging economies.

However, competition in the market for mobile devices became much more intense (even though Apple and Samsung still dominated industry profits) with the emergence of new competitors at the "low end").

Should Samsung start treating its mobile products most as "cash cows" rather than "rising stars" and refocus their significant investment in R&D into other product areas?

It's a fascinating discussion and it touches on two very important business concepts - corporate culture and shareholder value (in particular the returns that Samsung shareholders receive via their very low dividend yield).

Sunday, 7 January 2018

Ansoffs matrix

Check out this incredibly interesting (!!!) video explaining how to relate Ansoffs matrix to the business world.

More material on Ansoff below:

...and [perhaps the best one...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)